Heart Health

A planned approach using Heart Health Checks supports good Heart Health.

What is a Heart Health Check?

A Heart Health Check (absolute CVD risk assessment) is performed by a doctor. A Heart Health Check will mean your doctor can determine whether you have a low, moderate or high risk of having a heart attack or stroke in the next five years.

As part of a Heart Health Check, your doctor will:

- take blood tests (for your blood cholesterol and blood glucose levels)

check your blood pressure - ask about your immediate family’s heart health history (your parents and siblings)

- take into account other conditions you may have, such as kidney disease or arrhythmias

- ask about your lifestyle behaviours, about your diet, whether you smoke, how active you are, and

- assess your body mass index (BMI) and waist circumference.

Depending on your result, your doctor may discuss some lifestyle changes such as improving your diet, exercising more or quitting smoking. Your doctor may also prescribe medication to control high blood pressure or high cholesterol to reduce your risk. Or advise further tests to screen for diabetes. They will also advise when you are due for your next Heart Health Check.

If you want to discuss, further contact our Practice and meet with one of our GP’s.

Why assess absolute CVD risk?

The burden of cardiovascular disease remains high. Cardiovascular disease (CVD) in Australia:

causes one in four of all deaths1

claims the life of one person every 13 minutes1

accounts for 1,600 hospitalisations per day.2

Two-thirds of Australian adults are living with at least three CVD risk factors, such as elevated blood pressure, cholesterol and diabetes.

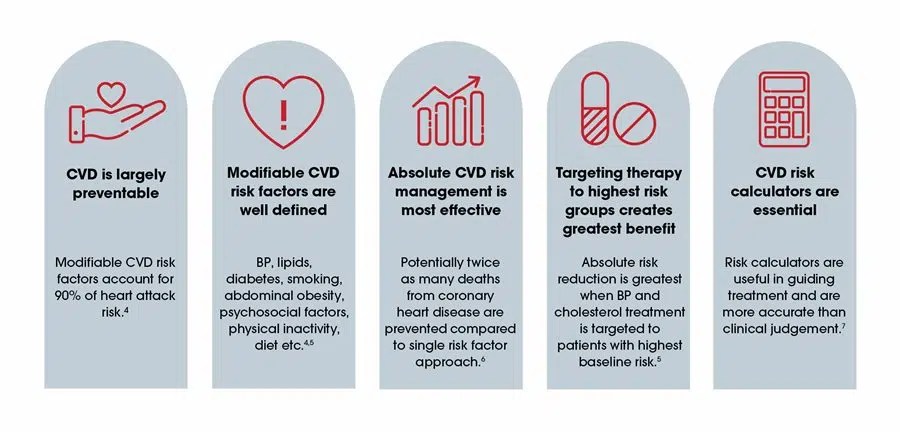

Absolute CVD risk assessment brings together multiple risk factors to give an estimate of combined risk of heart attack or stroke in the next five years. Modifiable CVD risk factors such as those mentioned above account for 90% of risk of heart attack, reinforcing the fact that CVD is largely preventable.

The absolute CVD risk approach?

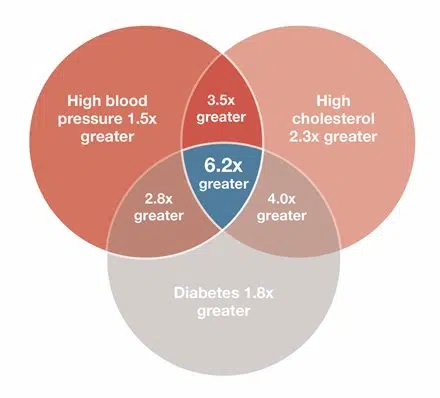

Absolute CVD risk assessment takes an integrated approach. It brings together multiple cardiovascular risk factors to give an estimate of the combined risk of experiencing a heart attack or stroke in the next five years (see Figure 1).

Creating even a moderate reduction in several risk factors is more effective in reducing overall CVD risk than a major reduction in a single risk factor alone.

Figure 1. An illustration of how individual CVD risk factors can combine to increase overall risk.

Since their launch in Australia in 2009, and update in 2012, the absolute CVD risk clinical guidelines have become the mainstay of treatment decision making for the primary prevention of CVD. However:

- there is still suboptimal assessment of risk factors

- 70% of high-risk individuals aged 45 to 74 years are not receiving guideline-recommended blood pressure and lipid lowering therapy.3

A planned approach using Heart Health Checks supports such interventions.

Absolute CVD risk principles

References

- Australian Bureau of Statistics 2019, ‘Causes of Death, Australia, 2018’, 2019.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, National Hospital Morbidity Database (NHMD), 2019; Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, ‘Australian Health Expenditure – demographics and diseases: hospital admitted patient expenditure 2004-05 to 2012-13’, 2017, cat. no. HWE 69.

- E Banks, SR Crouch, RJ Korda, B Stavreski, K Page, KA Thurber and R Grenfell, ‘Absolute risk of cardiovascular disease events, and blood pressure- and lipid-lowering therapy in Australia’, Med J Aust, 2016, 204(8):320, doi:10.5694/mja15.01004.

- S Yusuf, S Hawken, S Ounpuu, T Dans, A Avezum, F Lanas, M McQueen, A Budaj, P Pais, J Varigos and L Lishen , ‘Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study’, Lancet, 2004, 364(9438):937-52.

- National Vascular Disease Prevention Alliance, ‘NVDPA Absolute CVD risk guidelines 2012’.

- D Manuel, J Lim, P Tanuseputro, G Anderson, A Alter, A Laupacis and C Mustars, ‘Revisiting Rose: strategies for reducing coronary heart disease’, BMJ, 2006, Mar 18, 332(7542):659-62, doi:10.1136/bmj.332.7542.65.

- J Jansen, C Bonner, S McKinn, L Irwig, P Glasziou, J Doust, A Teixeira-Pinto, A Hayen, R Turner and K McCaffery, ‘General practitioners’ use of absolute risk versus individual risk factors in cardiovascular disease prevention: an experimental study’, BMJ Open, 2014, 4(5):e004812.